Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search results'Young Soeharto': Jenkins details potentially formative events in ex-president's early years

David Jenkins' biography of Indonesia's second and longest ruling president, Soeharto, is a comprehensive and compelling read, with at least two more volumes to follow.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

he first volume of David Jenkins’ long-awaited biography of the architect of modern Indonesia is now available from Singapore’s ISEAS Publishing.

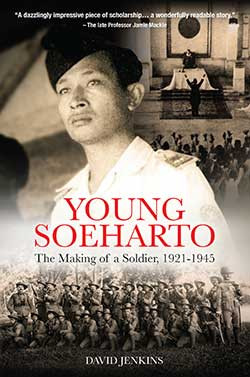

Released on June 30, 2021, Young Soeharto: The Making of a Soldier, 1921-1945 is a masterpiece. At once comprehensive and compelling, the biography will be a delight to serious scholars and armchair historians alike. While the massive volume runs 503 pages comprising 300 pages of text and over 150 pages of footnotes, bibliography and glossary, it also contains nearly 20 pages of photographs and is beautifully printed. The reader is carried easily on the Jenkins’ smooth prose, sharpened by the Australian journalist’s decades as a reporter and editor of note.

Despite the fact that Soeharto ruled Indonesia with an iron fist and an actor’s smile for 32 years and guided the country with ruthless determination from poverty to middle-class respectability, little is known about the man and the forces that shaped him.

“He was one of the most complex and important Third World leaders of the post-World War II era” Jenkins notes in the introduction, but Soeharto eschewed the egocentric myth-making common to many other long-serving charismatic despots like Mao Zedong, Kim Il Sung and Haile Selassie. The few biographies that were published during his lifetime offer many details about his accomplishments and hint at his personality and how he saw himself in later years, but provide only the barest of clues as to his daily life, the culture and career experiences that molded one of the greatest and most successful leaders of the 20th century – indeed, perhaps the last great Asian despot.

Jenkins came to Indonesia in 1969 as a young journalist and quickly scored a rare interview with Soeharto, who was just consolidating his power after the bloody transition of 1965-68 that brought down Sukarno, Indonesia’s charismatic independence leader and first president, and ushered in Soeharto’s New Order. This first interview was to evolve into a lifetime of research and analysis.

I first met Jenkins when I was freelancing in Jakarta in the late 1970s. He had returned as the correspondent for the legendary Far Eastern Economic Review. During his time in Indonesia, he developed a tremendous stable of contacts and sources and established personal relationships, not only with prominent figures but also many more obscure individuals who had known Soeharto in his early years.

Jenkins is no newcomer to world of academic publishing. His first book, Soeharto and His Generals, was published in 1984 to some acclaim. His latest book has at least three tremendous strengths in addition to its deep scholarship. The author displays both a comprehensive grasp of history and a keen insight into the conditions of Soeharto’s life at each stage. He then blends the two into a seamless tale that traces the arc of Indonesian history, starting with the final throes of Dutch colonialism and on through the turbulent yet liberating Japanese occupation, to the formation of a nascent Indonesian military and ultimately, to the 1945 declaration of independence.

All the while, Jenkins locates the young Soeharto along that arc and describes his evolution from a ragtag village boy whose greatest pleasure was riding water buffaloes in the rice paddies into a young bank clerk, a soldier in the colonial Royal Netherlands Army (KNIL), a lucky recruit into the Japanese police and, finally, an early member of Pembela Tanah Air (PETA) or “homeland defenders”. This was the fledgling military force created by the Japanese that would evolve into the Indonesian Armed Forces (ABRI), the national military of a newly independent Indonesia that has played a key role at virtually every critical juncture in the country’s history.

Abandoned by his mother shortly after birth, Soeharto’s childhood was chaotic, not to say traumatic. His mother reappears in impoverished circumstances with a new husband when he is four. His thrice married, absentee father (Soeharto had six half brothers and half sisters on his father’s side) drifted in and out of his childhood, moving him from relative to relative as he deemed appropriate, but never, it seems, bringing Soeharto into his own household.

He reappears when Soeharto is 9, declaring that he is disappointed with Soeharto’s schooling and whisks him off without a word to his mother (Soeharto once used the word “kidnapped” to describe the incident) and drops him off with the family of a sister married to an agricultural officer of the priyayi (aristocracy), where Soeharto could get a better education. This is ngenger, a Javanese form of adoption under which a child lives with a relative and does chores in return for room and board.

“At nine, Soeharto was cut off almost entirely from his family and friends, sent to live first with an aunt and uncle, then with a succession of foster families, some of whom, it has been claimed, were to treat him harshly.” (Young Soeharto, p. 59)

Through it all, Soeharto proved resilient and evolved into a clever young man, ever cautious and calculating. But according to many who knew him later, he never forgot the treatment that he received, both good and bad. “As a boy, Soeharto seems to have been quite insecure, grateful for small acts of kindness, yet brimming with resentment towards those who had slighted him, always conscious of scores that needed to be settled.” (p. 55)

Based on comments in Soeharto’s memoirs, Jenkins concludes: “Soeharto’s recollections of his maternal great grandmother are … a study in resentments nurtured for more than sixty years.” (p. 55) Later, he writes: “It is impossible, reading through the various accounts that Soeharto gave of his childhood, not to be struck by the way in which he wrote his parents out of his life.” (p. 121)

Jenkins also traces the roots of Soeharto’s proclivity for Kejawen (Javanese animist faith) and his early mistrust of political Islam, although these views may have moderated later in life. He then follows Soeharto’s entry into the KNIL just before his 19th birthday in June 1940, shortly after the Dutch surrendered to Germany.

It was in the military where Soeharto was to find his home at last and receive the training that was to serve him so well later. Jenkins quotes Soeharto from an interview published in early 1998 in a Japanese publication: “We were drilled from morning till night … but I liked it … I realized I was suited to the disciplined life of the military.” (p. 125)

By November 1942, Soeharto had recovered from a bout of malaria and the Japanese were seeking Indonesian police recruits. Soeharto decided to risk applying – risky, because the Japanese were arresting former KNIL members. In the event, the Japanese did not immediately discover Soeharto’s KNIL past. He passed the exam and was accepted into the police force, where he received more training. Then in late 1943, the Japanese decided to form PETA and began to recruit cadets, many of whom would later become high-ranking officers in the future Indonesian military. Among them was Soeharto.

As in the rest of the book, Jenkins is masterly in his treatment of the behavior of both Japanese and Indonesians as defeat loomed for the former, and includes information from interviews with former Japanese soldiers who were Soeharto’s superiors and remembered him well. Indeed, another one of the book’s strengths is the knowledge gleaned from Japanese sources.

We are reminded throughout this period that Soeharto had finally entered a world in which he would thrive and one which clearly shaped his later behavior as Indonesia’s unchallenged ruler for 30 years, “a world in which discipline was rigid, brutality a fact of life, paternalism taken for granted and police influence all pervasive”. (p. 298)

There is little doubt that Soeharto’s pedigree and education were far beneath that of the very few among the young Indonesian elite who had the benefits of a Dutch education, like Sukarno, Mohammad Hatta and Abdul Haris Nasution. But as Jenkins tellingly notes, when Indonesia declared independence in August 1945, the 24-year-old Soeharto “had more military training by far, and more military experience than perhaps 98% of his fellow PETA officers, the men who would form the backbone of the new national army”. (p. 304)

And here the book concludes, leaving the reader hungry for the promised volumes two and three that will take us through the early years of independent Indonesia, the deadly turmoil of the 1960s and Indonesia’s economic rise to middle income status under Soeharto until he resigned in May 1998, amid the pressure and instability generated by the Asian financial crisis.

David Jenkins. Young Soeharto: The Making of a Soldier. Singapore: ISEAS, 2021.

***

The writer is a businessman who has lived in Indonesia since 1977 and worked as a freelance journalist in 1978-1981. His obituary of Soeharto was published on Feb. 1, 2008 in Singapore’s The Business Times.