Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsEducation and Islamic authority

Around 90 percent of Indonesia’s 260 million citizens are Muslim. Most of them support the idea that Islam should have a public rather than private presence in everyday life, and for that reason, Islamic authority is not just an abstract for Indonesians; it has practical effects. But just what kind of role should Islamic authority play in public life?

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

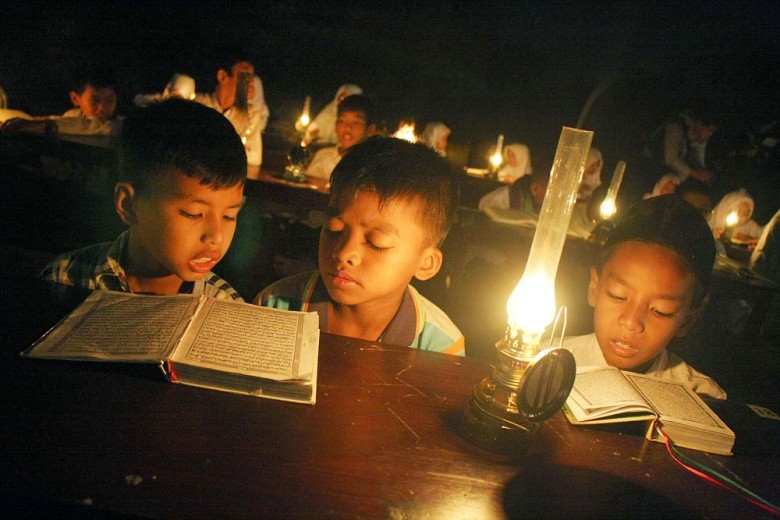

A major strategic goal has been the creation of an Islamic higher education system. This was achieved by revising the range of Islamic sciences and expanding it beyond the core sciences that had previously sustained Islamic education (Arabic grammar, law, Quranic interpretation, theology, etc.). (JP/Ganug Nugroho Adi)

A major strategic goal has been the creation of an Islamic higher education system. This was achieved by revising the range of Islamic sciences and expanding it beyond the core sciences that had previously sustained Islamic education (Arabic grammar, law, Quranic interpretation, theology, etc.). (JP/Ganug Nugroho Adi)

A

round 90 percent of Indonesia’s 260 million citizens are Muslim. Most of them support the idea that Islam should have a public rather than private presence in everyday life, and for that reason, Islamic authority is not just an abstract for Indonesians; it has practical effects.

But just what kind of role should Islamic authority play in public life?

This is a topic that has concerned Indonesian policymakers since before the country became independent in 1945, and this concern has shaped Indonesian Islamic society in distinctive ways.

In 1945, when the founders of the Indonesian state were thrashing out the newly independent nation’s constitutional arrangements, a decision was made to establish a religious affairs ministry.

Education was central to the ministry’s brief, and for good reason: in the early days of Indonesian independence, Islamic education was falling behind the nonreligious educational system in its appeal to Muslim Indonesians. The rising appeal of “modern education” threatened the future of Islamic authority in the country.

The ministry began fashioning an educational system that would maintain relevance beside the nonreligious education being offered through the Culture and Education Ministry. Looking back over the developments since 1945, two distinctive strategies appear as the most prominent.

A major strategic goal has been the creation of an Islamic higher education system. This was achieved by revising the range of Islamic sciences and expanding it beyond the core sciences that had previously sustained Islamic education (Arabic grammar, law, Quranic interpretation, theology, etc.).

In the present, Indonesia’s state Islamic universities and institutes of higher Islamic learning teach not only traditional Islamic subjects, but have also appropriated “secular” disciplines such as the social sciences, history, media and communications.

The broad definition of Islamic study in these institutes has been supported by the equally broad range of qualifications of their staff. Some of them are trained in traditional centers of Islamic learning such as Cairo’s Al-Azhar mosque university, but many are graduates of social sciences departments in Europe, the United States and Australia.

This educational innovation has had a pronounced effect on contemporary Islamic authority. Many of the staff of these institutions are prominent as public commentators, and their contributions to public debates frequently bring a broader, social perspective to issues that might otherwise be resolved in strictly religious deliberations.

Further, their contributions have legitimacy as Islamic ones, for members of the public realize that these experts hold positions in educational institutions that are explicitly Islamic.

As a result, in comparison with other Muslim-majority countries, Indonesia has a broader range of Islamic authorities bringing differing perspectives to public debate and policy. Without the institutional context created by the ministry, this might not have happened.

A second innovation has been to bring traditional Islamic schools at primary and secondary levels into the orbit of contemporary education.

In the pre-independence period, for many children in the Netherlands Indies, an Islamic education was the only form of education available. These students attended educational institutions managed and owned by people learned in the Islamic sciences or ulema.

In recent decades, the Indonesian government has made it a priority to bring these institutions — which are valuable to Indonesia’s social fabric because of their religious legitimacy and the sheer numbers of Indonesians they educate — into the state-regulated system.

This has not been an easy task due to many problems: a shortage of qualified staff and resources to pay them; the costs of constructing and maintaining infrastructure; the difficulty of expanding traditional curricula to embrace contemporary subjects; and a widely-felt concern that the core Islamic subjects would fall by the wayside in the process of assimilation.

Nevertheless, great gains have been made. Most Islamic schools now offer religious subjects alongside “nonreligious” curriculums that enable graduates to continue to higher education and employment. These gains have benefited the sector: many parents prefer to send their children to Islamic schools.

They not only have confidence in the discipline and values that are central to Islamic education but also feel assured that their children will receive an education that has contemporary relevance.

The educational innovations of the Religious Affairs Ministry have made a difference in the present. Islamic education has remained a viable element of Indonesia’s educational system, and Islamic authority is spread over a wide range of actors with varying involvements in contemporary life.

***

Associate professor of anthropology at the School of Social Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, with major projects focusing on an intercession ritual popular in West Java; Islamic preaching and everyday life; commemoration of subnational Islamic legacies; and the distinctive meanings of practice in times of rapid change