Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsNon-Aligned Movement: The way forward

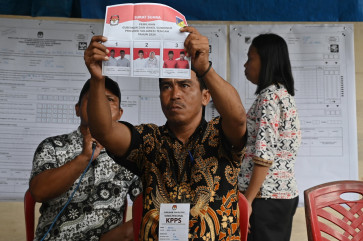

Indonesia hosted a ministerial meeting of the Non-Aligned Movement, in Bali recently

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

ndonesia hosted a ministerial meeting of the Non-Aligned Movement, in Bali recently. The meeting discussed a wide range of issues of common concern and agreed on some important outcomes. The meeting also marked the 50th anniversary of the movement.

At 50 years old, NAM is one of the oldest post-war international forums founded at the height of the Cold War. It survived the Cold War and charted a different avenue for inter-state relations, and continued to exist and play a role in the post-Cold War era.

Since the end of the Cold War, there has been unanimity among its members about the persistent relevance of the movement. Indonesia affirmed this unrelenting pertinence when it chaired the movement in 1992, and reaffirmed it consistently at many past meetings including the recent ministerial meeting.

Some quarters outside the Movement, however, have expressed doubts about the movement’s significance. Some said that NAM was nothing but a Cold War relic. Others said NAM represented the interests of only some its member countries.

All NAM members have often been dragged along by the interests of a few member countries that are more outspoken and assertive than others. For this reason, the late ambassador Richard Holbrooke urged African countries to break away from the Movement.

Before he left his post as the US Representative to the UN in New York in January 2001, Holbrooke said the NAM did not serve the interests of Africa.

From a standpoint of membership, the question of relevance no longer casts doubt. At the ministerial meeting in Bali, NAM members included 120 countries, with Fiji and Azerbaijan recently joining.

Although NAM does not have institutional formality like other post-war institutions such as the United Nations, the Bretton Woods institutions, or NATO, remarkably it has managed to collaborate and make a lot of achievments through consensus. This is one of the NAM strengths.

As NAM is entering the 21st century, it is facing new realities both inside and outside. While NAM comprises least developed and developing nations, many of its member countries are now emerging, such as Indonesia itself.

Their power on the global stage is increasing, both economically and politically. This will certainly be an asset to the movement.

But, will the movement survive and be able to shape the future in another 50 years?

It will, if first it diversifies its leadership. Since 1961, NAM’s chair has been decided on a geographically rotating basis. So far, four countries in Asia have assumed the chairmanship position (Sri Lanka, India, Indonesia and Malaysia) and Iran is set to chair it in 2012; six countries from Africa (the United Arab Emirates, Zambia, Algeria, Zimbabwe, South Africa and now Egypt), one from Europe (Yugoslavia — twice), and two from Latin America (Cuba, Colombia and Cuba again).

NAM’s chairmanship and leadership needs to go beyond this pattern. NAM may wish to anticipate the fact that in the future, Chile, Jordan, Singapore or Vietnam or elsewhere should chair and lead the Movement if they wish to do so. Diversity in leadership will enrich NAM with traditions in governance.

Second, greater visibility in solving global problems is another important element of NAM’s constant relevance. Critical to this visibility is leaders’ innovation in finding solutions.

The chair of the movement may wish to use good offices or advisory offices, leader’s missions, leader’s special envoys, leader’s sherpa, ad-hoc task forces, confidence-building missions, or contact groups in helping resolve global and regional conflicts and disputes.

The present situations in Libya, North Africa and the Middle East, and of course the protracted Arab-Israel conflict, seem to call for such initiatives.

Critical to the external relations and global contribution of NAM and its member countries is a realistic and pragmatic approach guided by principles, in particular the Bandung Principles. Those principles are the soul of the Movement that distinguish NAM from other cooperation arrangements.

Third, it is important for NAM to make more deriverables in the future, both in dispute settlements among its members and meeting their economic and development needs. Conflicts and disputes still take place within and between some NAM member countries.

Poverty remains a serious matter in many NAM countries. When compounded by conflicts that are fuelled by illicit trade of small arms and light weapons, freeing peoples from wants becomes a very daunting task.

NAM needs to go beyond conference room deliberations in catering to the fundamental needs of the peoples of its members. It needs to go beyond the lengthy and thick final documents that are traditionally adopted at the end of a NAM Summit or ministerial meeting.

Fourth, NAM will need greater unity of voice in responding to future challenges. Unity of voice also reflects strong leadeship and strong cohesion of the movement.

When NAM member states speak with one voice, it will have a better chance to achieve a symmetrical result in its diplomacy.

Fifth, in the present and future world where government is no longer the only actor that decides the fate of NAM, the cause of the Movement will be strengthened when it enjoys unflagging support, let alone active participation, from its peoples.

Therefore, NAM might also wish to explore greater contribution of business sector and civil society groups from each of its member countries for the enhancement of NAM cooperation.

And sixth, to support all the conditions mentioned above, unrelenting efforts to improve NAM’s working methods — from Cartagena methodology to the post-Zimbali reform, are essential.

Indonesia’s chairmanship of NAM in 1992 laid the foundation for better working methods so that the movement could be well calibrated in the wake of the post-Cold War era. The 21st century sets a stage for more effectice and efficient NAM methodology.

A new generation of NAM is about to emerge as the 21st century is unfolding. It is carrying with it new hopes and new challenges.

All NAM’s member countries are called upon to ensure a seamless revival of the movement into the new century. I am fully confident that Indonesia and its role, as always, will remain pivotal to the renewed NAM.

The writer is assistant special staff to the President for international relations. The opinions expressed are personal.