Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsThe grim portrait of Nona Djawa

Survivor: Sri Sukanti with her family and dogs at her home in Karanganyar, Central Java

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

S

span class="inline inline-center">Survivor: Sri Sukanti with her family and dogs at her home in Karanganyar, Central Java. Sri was one of the jugun ianfu (comfort women) during the Japanese occupation period in Indonesia.

The old woman recounted her gloomy past with trembling lips and erratic breaths, wiping her tears now and again. Her wrinkled face seemingly concealed her bitter experiences.

“For four days, I was forced to accommodate his desires. I wished I was dead. I was no longer human,” she revealed.

She is Sri Sukanti, 81, one of the jugun ianfu (comfort women) during the Japanese occupation period in Indonesia. She told her story in a talk, film screening and photo display entitled Nona Djawa: Di Balik Rekrutmen Sistem Perbudakan Seksual Militer Jepang di Indonesia 1942-1945 (Javanese Maidens: Behind the Japanese Military’s Sexual Slave Recruitment in Indonesia 1942-1945), at Balai Soedjatmoko, Surakarta, Central Java, March 8-12.

In the program organized by The Global Review and Jejer Wadon Community to mark International Women’s Day, Sri talked about how Japanese soldiers kidnapped her and locked her up for four days in their headquarters, Gedung Papak, Purwodadi, Central Java. She was only nine, but Ogawa, a Japanese soldier, raped her for four consecutive days.

“I was sent home when Japan surrendered to Allied forces. I never saw Ogawa again,” she said. Free from Gedung Papak, Sri didn’t automatically live better. She was ostracized by her neighborhood for years. At school, she was called bekas kethek (a former monkey mate).

She married twice, but a doctor found that she was not capable of having children due to impairments to her womb. Sri had to strive hard for her family by working as a sand porter, masseuse and for the last 10 years she has been bathing corpses.

Powerless: The face of a former comfort woman.

Sri was not alone. On the exhibition walls were over a dozen images of other Javanese girls. Wainem, 88, from Karanganyar, Central Java, for instance, was one of them. Through rather blurred close-up pictures, photographer Meicy Sitorus depicted the murky tales of these women.

Wainem was 20 when she was transported with many other young women from Karanganyar on a truck to Solo (Surakarta). They were meant to be employed as washers, cooks and gardeners. But in the military barracks, Wainem was raped by 10 Japanese soldiers and forced to serve as an ianfu.

From Solo, Wainem was then moved to the military quarters in Yogyakarta. After Japan’s defeat, Wanem returned to Karanganyar penniless. Mardijah from Banyubiru, Ambarawa, Central Java, was snapped against the background of Japan’s barracks in Ambarawa, where she had been raped.

Evidence: Kebaya (traditional long-sleeve blouses) worn by Javanese maidens during the war period are on display. Given the ianfu name of Momoye, Mardiyem from Yogyakarta, according to the display’s catalogue, claimed to have been forced to serve at 13. Her baby was aborted when she was 15 without anesthesia, by pressing the infant out of her uterus. The years of torment inflicted sexual trauma on Mardijem, who died in 2008 at 78.

A total of 80 photos were on display, presenting fragments of the daily lives of 13 women, who about 70 years ago, were compelled to become ianfu. Taken from simple angles, Meicy’s pictures focused on the daily activities of these women in their advanced age with their families.

Some shots portrayed ianfu tracing their gloomy-day locations, including Japanese military quarters, along with the photographer and researchers. There were also photos of the women’s war-time clothes, and an advertisement in Malay seeking Javanese maidens published in Pewarta Perniagaan on Feb. 16, 1943, besides snaps of fragmentary parts of their bodies like the foot, face, back and arm, apparently meant to give a touching impression.

Visitors followed the story of the comfort women to grasp the message of the historical episode mostly through picture captions as the exhibit did not comprise your average works of art, which usually communicate their “beauty” directly to observers and enthusiasts.

The screening of a documentary, Nyah Kran Tawanan di Gedung Papak (Gedung Papak Detainee Nyah Kran), directed by Ivan Meirizio, also provided guests with a better understanding of the women’s past circumstances. This film was shown throughout the program on a television set placed in the middle of the display room.

The Nona Djawa accounts, buried for around 70 years, were unveiled by Eka Hindra, an independent researcher of Indonesian ianfu, along with Jo Cowtrae, Ivan Meirizo, Becky Karina, and Meicy. Since 1999, they have studied the practice and system of sexual slavery by the Japanese military in Indonesia from 1942 until 1945, by digging into the lives of former ianfu. Over a period of 14 years, the researchers interviewed 13 “Javanese maidens”.

The research efforts were motivated by the courage of Tuminah, who in 1992 was the first to publicly testify about her experience as an ianfu. This program was dedicated to Tuminah’s audacity.

“Tuminah’s confession and testimony was first heard by Koichi Kimura, a theologian from Japan. It was later published as a series of articles in a local newspaper in the same year,” said Balai Sudjatmoko spokesman Yunanto Sutyastomo.

Eka said after beating the Allied troops in 1942, the Japanese military wanted to make the Indonesian archipelago a human resources zone to support the victory of the Asia-Pacific war. From that time, Japan gathered men to become romusha (forced laborers), while women were forced to serve the soldiers.

“Nona Djawa constituted a sacrifice for independence that was previously unheard of and whose fates have since escaped attention. People need to understand that the ianfu women were war victims,” noted Eka.

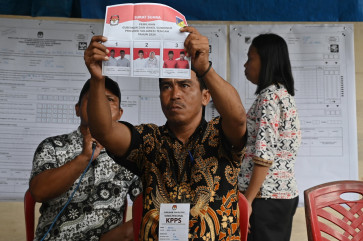

Never forget: Visitors view photos of former jugun ianfu at Balai Soedjatmoko, Surakarta, Central Java,

According to Eka, young women at the time were captured from their villages and detained in Ianjo (a kind of brothel) strictly guarded by Kenpeitai (Japanese military police). Each lanjo room was given a number and a Japanese name.

Through the research, Eka uncovered historical evidence of traceable atrocities carried out against Indonesian women. “The core point is that these young women became ianfu out of force. They were not given a choice,” added Eka.

Before being exhibited in Solo, Nona Djawa was shown at Cornell University, US, in 2012. Instead of just opening old wounds and exposing the cruelty of war, the program was intended to impart the historical fact of women being victimized by war.

“The exhibition is meant to acquaint the younger generation with the dismal affair of history Indonesian women had to experience. War has not only caused physical ravages but also ruined the values of humanity,” said Ivan Meirizio, director of the Gedung Papak documentary.

— Photos by Ganug Nugroho Adi