Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsBeting village: Trapped in an ingrained narcotics ecosystem

The floating settlement of Kampung Beting in Pontianak, West Kalimantan, is a complex warren of factors that have contributed to an entrenched drug trade that few residents, if any, have been able to escape.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

This is Part 2 of a two-part story on Kampung Beting.

Read also: Beting village: Haven for drug users, hell for non-users

Maze with a purpose

The only land access to the floating settlement of Kampung Beting is over gertak, footbridges made out of ironwood suspended above its many waterways. Adding to the challenging accessibility are the mazelike, crisscrossing narrow alleys of Beting village, truncated only by the Kapuas River. All houses connect through concealed doorways.

According to Arief Nugroho, a Pontianak Post journalist who reported on a police raid in 2012, this interconnected architecture and winding geographical layout contribute the single greatest hurdle to unraveling the tangled threads of the local narcotics ecosystem. The village layout makes it easy for dealers to escape and hide, even get rid of evidence, in matters of seconds during a police raid.

Before he switched to steering canoes, Randy (not his real name) worked as a “messenger” for dealers. His wages depended on each dealer’s "generosity", he says, and usually ranged from Rp 50,000 to 100,000 a day.

Randy and other messengers kept watch at the village entrance, reporting to the dealers whenever someone unknown or suspicious arrived, including policemen. If this happened, Randy would repeatedly strike an electricity pole as hard as he could. The sound was an alarm for residents to gather and get ready to defend themselves.

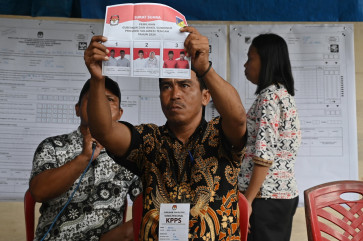

Trapped by drugs: a young man waits for visitors who need him to guide them to dealers. (JP/Reza Darwin)According to Denny (not his real name), one of the most notorious drug dealers in Kampung Beting, communal solidarity was the norm. With few jobs to go around, the people of Beting were united by their anger at a government that seemed to care little about them, rarely checking on their needs or providing solutions, except during raids and public relations visits.

Denny, who is in his 60s, says that he shares his fellow villagers' fears over the dangers of the drug trade compounded by the lack of jobs, but doing it anyway, knowing that it could very well cost him his life.

"What else do they want or let me do besides this? I wish for nothing but to protect my business and the other residents. We are poor, but who cares about us? Who feeds us? No one but ourselves. We are bound together to survive,” Denny said, casting his eyes over the Kapuas River.

“I'm tired of this game of cat and mouse. I'm old. I don't want my children and grandchildren to be like me. Let them work in an office."

Shackles of drugs

Chairil Anwar, director of Bumi Khatulistiwa, a center he set up in 2013 to provide community-based rehabilitation (RBM) treatment for drug users in Pontianak, concurs with Denny.

"If you look at it, the economic condition of the people there [Beting] is very vulnerable. They're just a market; they’re all small-scale traders. Major dealers wouldn't possibly want to live in a slum like Beting. So they are just victims of social stigma," said Chairil.

He pointed out that the children of Beting were used to "seeing people using drugs” every day, and that this environment created drug addicts at a very young age. And while many dealers brought their children to Bumi Khatulistiwa, it was often a temporary solution because after rehab, they would inevitable return to a home environment of rampant drug use.

"The problem is complex," Chairil stressed.

There is also a lack of rehabilitation facilities. The one Chairil runs is limited in both space and resources.

"People have to go to Batam, to Jakarta, to other cities to get well,” he said. “I wish the rehab [treatment] was free, but it's not possible because we don't have much financial support.”

On the river: A floating village, Beting's complex accessibility makes it easy to hide and trade drugs. (JP/Reza Darwin)It isn't clear when and how Beting became the drug hub that it is today. Denny recalls that even in the ‘80s, it was already overrun by narcotics. The only thing he knows is that almost all the drug supply, especially crystal meth, comes from Malaysia. He agrees with Chairil that Beting is nothing more than a market. There are no drug factories in the vicinity.

Like Chairil and Denny, Randy is also despondent. He can't find a way to free his life from the shackles of drugs. Randy recently made up his mind to move to another area in Pontianak, primarily to change the address on his citizen ID card and escape the social stigma attached to Beting so he can find a decent job. He says he dreams of moving his family out of Beting so they can live like an "ordinary" family.

"I only want my younger siblings to go to school, work and have a future. This unfortunate fate should stop with me, my father and my brother. I still love my hometown with all its sins. But I don't want to be there forever," he said, softly.