Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search results'Invisible Hopes': A real look at the lives of female inmates and their prison-born children

Depicting the harsh realities of life for female inmates and their children born in prison, the documentary film reveals a complex problem of the correctional system.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

“Please open the door!” several children cry as they grip and shake the bars of the door to their cell. They wait every day for a prison officer to let them out of the narrow, crowded space they share with dozens of adult female inmates and their children.

They are the children of female prisoners who were born and are being raised in prison, which has effectively robbed them of a normal childhood.

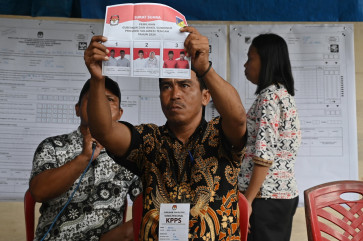

Invisible Hopes is a full-length documentary by Lam Horas Film that depicts the harsh reality of life behind bars for these children and their incarcerated mothers. Shot mostly at Pondok Bambu female penitentiary in East Jakarta, the documentary film follows the lives of several inmates, some pregnant, their children and the daily hardships they experience.

L, a former inmate in her 30s, explained the struggles she went through while she was pregnant in prison at a media event for Invisible Hopes on April 1, 2021 at Plaza Senayan.

“My family lived so far away and I had no visitors,” she said. “I had to wash the clothes of other prisoners to make money to buy diapers, [formula] milk and food for my baby.”

Director Lamtiar Simorangkir said she realized she had to make the documentary when she met an 18-month-old child in an adult prison while she was doing research.

“We were having fun, just talking with each other, but when the prison bell rang, she suddenly gave me a goodbye kiss and left to join the others in [her] cell,” recounted the 42-year-old director.

“It made me want to cry, the fact that since [she was] very little, she had to live the life of a prisoner.”

Difficult project

Lamtiar acknowledged that getting all the necessary permits for filming at the prison was an extremely difficult and long process.

“You have to get permission from the Law and Human Rights Ministry’s corrections directorate general first,” she said.

The director, however, managed to get some help from the National Commission on Violence Against Women (Komnas Perempuan), which had provided support on her previous short film Lamtiur (Brighter), about a Batak woman trying to break free of cultural and gender oppression and finding her own path.

The production also received funding from the Swiss Embassy and the Norwegian Embassy.

Even after they had the permits in hand, Lamtiar and her team still had to convince the prison warden, officials and of course, the inmates, to be involved in the production, which was no easy task.

“The prisoners were suspicious of us at first,” she said. “They thought we were working with the police.”

It took a while, but the inmates started to come around to the idea. It started with a couple of prisoners, but more and more approached Lamtiar to tell her their stories each day.

The director also made some personal sacrifices so Invisible Hopes could happen.

“When we started shooting, I had to skip work a lot to go to the prison and I got fired for it,” she said, laughing. “I also sold my car to fund the first 6 months of production.”

Complex problem, no easy solution

According to Enggarfaesti Sinara Sukma of the Legal Aid Institute in Bantul, Yogyakarta, laws and regulations already exist on pregnant inmates.

“Pregnant prisoners have the right to supplementary foods (of an additional 300 calories per day) and medical checks by a specialist for their babies until the child turns 2 years old,” said the junior associate lawyer.

The implementation of these regulations is still questionable, however, and varies from prison to prison.

“The execution is lacking, possibly due to lack of a budget, facilities or human resources,” said Sukma.

Maidina Rahmawati, a researcher at the Institute for Criminal Justice Reform (ICJR), said that while normative regulations on the nutritional requirements for mothers were in place, “other needs such as clothing and other children’s rights have yet to be regulated specifically”.

Meanwhile, Lamtiar pointed out that the issue was a complex one that didn’t fall under the responsibility of a particular institution.

“From the perspective of the Law and Human Rights Ministry, they have done their job, which is to rehabilitate prisoners,” the director said.

“But what about child care? That falls with the Ministry of Women Empowerment and Child Protection,” she continued. “Health issues? That’s the Health Ministry [...] and child protection? That’s a job for Social Services.”

Lamtiar added that a one-size-fits-all solution wouldn’t work: “Suppose a child born in prison is taken out of the institution. Who takes care of it? Many of the prisoners’ families can’t or won’t do it. Also, what about their need for breast milk? If the state takes up the care of these kids, what about their relationship with their mother? The psychological impacts the separation might cause? But if they’re allowed to live inside the prison, what about their living conditions?”

For these reasons, Invisible Hopes didn’t offer a solution, but rather aimed to portray the real issues.

Lamtiar said she hoped that the documentary film would agitate viewers, open dialog and in the long run, bring about better change for the vulnerable behind bars.

“We made the movie out of love for the pregnant women and children born in jail,” she said.

Invisible Hopes is scheduled for general release in May. Watch the official trailer.