Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsThe truth behind Freemasonry in Indonesia

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Tracing the history and heritage buildings of Freemasonry in Jakarta.

Many mysteries surround Freemasonry. The reportedly secret society has been rumored to be made up of devil worshippers who conduct wild orgies within their rituals. Members are said to be high-ranking officials surreptitiously working together for a certain grand design.

There may be little to no truth behind these rumors. But this organization used to flourish in Indonesia. And their legacies still stand in major cities in the country, including Jakarta, offering a glimpse into the highly exclusive fraternity.

“Freemasonry is actually an organization aimed at building character,” Sam Ardi, historian and Freemasonry researcher, said during a phone interview on May 27. Their teachings run across all SARA [ethnicity, religion or race]. They want to enlighten themselves and others all around them.”

According to the historian, the organization entered Indonesia in the 16th century together with many Dutch soldiers that were also its members.

“As many Dutch soldiers were also Masons, they congregated and formed Vrijmetselarij [in Dutch, Freemasonry] in the Dutch East Indies,” Ardi said.

Ancient symbols

Some of their traces can still be seen in Taman Prasasti Museum in Tanah Abang, Central Jakarta.

The museum, which used to be a Dutch cemetery, exhibits over 1,300 tombstones made of solid stones, marble and bronze. All the bodies buried in it were moved to another location when it was made into a museum in 1974.

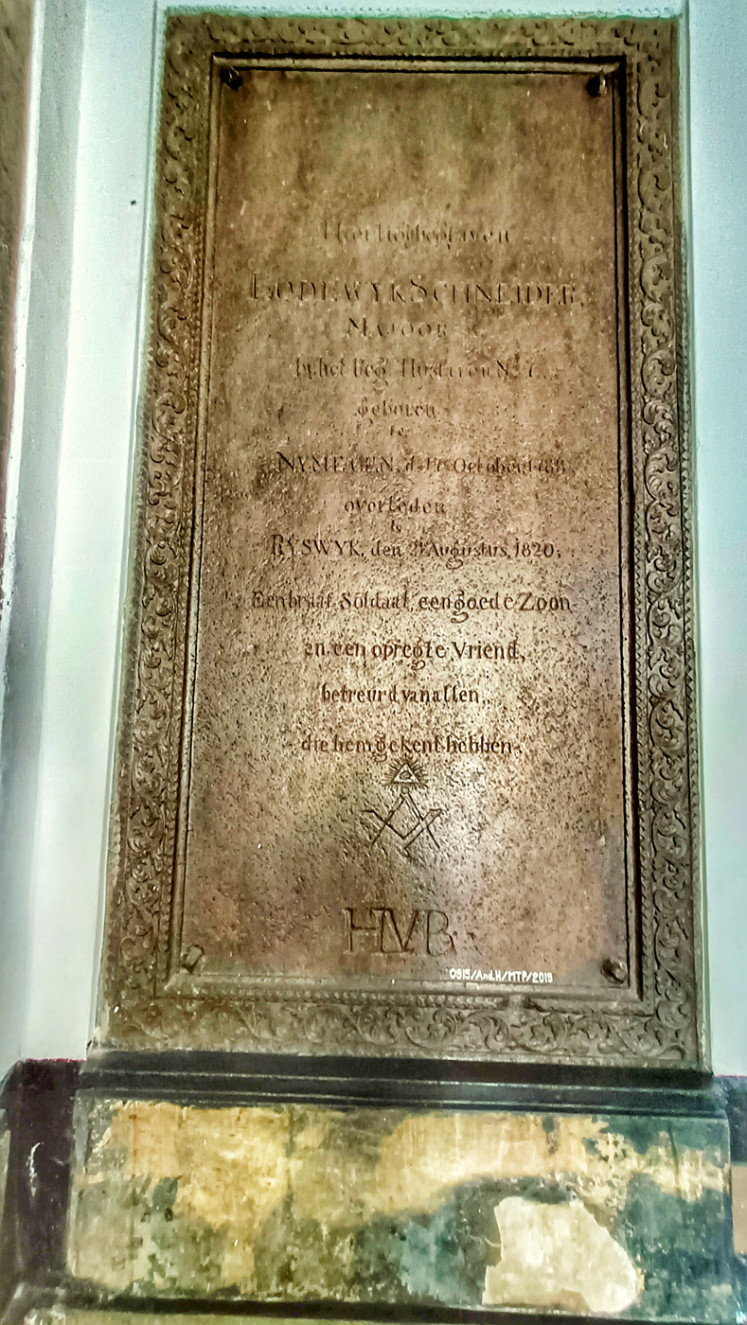

Near the entrance is a huge bronze gravestone of Major Ludewyck Schneider, who died in Ryswyk (now Lapangan Banteng) in 1820. Just below a brief testimony of the man being a brave soldier and a good friend is the symbol of square and compasses, topped with the All-Seeing Eye.

“The society uses the symbol of the builders [square and compasses], as they take on [the builders’] philosophy,” Ardi said. “The Masons are also building [something]. They’re building a temple of humanism.”

Initially, it was dark rumors about Freemasonry that made Ardi curious about the organization. The scholar then conducted in-depth research about the society in Indonesia and Netherlands.

“I discovered so many archives, books, journals and magazines about them,” Ardi said. “I even found the old certificate of [Thomas Stamford] Raffles being pledged [as a member of Freemasonry] in Java.”

Raffles was pledged as a Mason in Buitenzorg, now Bogor, in July 1812 after he was appointed as the lieutenant general during the British rule in Indonesia.

In Taman Prasasti Museum, we can also discover the former graves of Raffles’ wife, Olivia Mariamne, and his trusted counselor, John Leyden.

A stone’s throw away from their graves is the tomb of Batavia’s pawnshop and land survey office head, JH Horst. Even though he was not an architect, Horst was assigned to design Willemskerk (Willem’s Church) on Jalan Medan Merdeka Timur, Central Jakarta, in 1834.

When The Jakarta Post visited the Taman Prasasti Museum on April 24, someone had laid fresh flowers on JH Horst’s former grave. When we looked closely, we could see a huge skull and crossbones etched on his tombstone.

“The symbol represents one of Freemasonry’s teachings, Memento Mori [in Latin, Remember Death],” Arifanti “Mochi” Murniawati, a guide of Walkindies, a travel agent that conducts the Secret Society of Batavia tours, said.

Willemskerk, which boasts a grand dome, tall pillars and an Oculus ceiling, was initially reserved for high-ranking Dutch officials during the colonial era. Today, it houses GPIB Immanuel Jakarta.

Legacy: Some traces of Freemasonry can be found at Museum Taman Prasasti, including a tombstone that bears the square and compasses symbol. (JP/Sylviana Hamdani) (JP/Sylviana Hamdani)'Rumah Setan'

Freemasonry establishes local organizational units, called a lodge, in every country they settle.

During the colonial era, there were more than 20 Freemasonry lodges in the archipelago.

Many of these lodges were designed like ancient Roman temples with grand pillars adorning their façade.

Back then, many Indonesians nicknamed these lodges “rumah Setan” (Satan’s House).

“It’s actually a matter of mispronunciation and misunderstanding,” Sam Ardi said, with a laugh.

One of Freemasonry’s patrons is Saint John, or in Dutch, Sint Jan.

“To local ears, Sint Jan sounds a lot like Setan,” he added.

Among the first Freemasonry lodges in the Dutch East Indies was De Ster in het Oosten (The Star in the East), which was built on the Vrijmetselaars Weg (in Dutch, the Freemasons' Road) in Batavia in 1830.

Today, the same building houses a Kimia Farma branch office.

“There used to be an Eastern Star emblem on top of the building,” Mochi, the tour guide, said. “But it’s been removed now.”

During the tour, Mochi also showed a picture taken from the internet, which showed a Freemasonry ritual for new members. In the picture, a new member, his eyes covered with a handkerchief, was carried by senior members above their heads, resembling today’s moshing at rock concerts.

“Freemasonry uses rituals as role play to instill its values among members,” Ardi said.

Today, the road in front of the former lodge is named Jalan Budi Utomo.

Coincidentally, some of Budi Utomo’s chairmen and members have been confirmed as Masons. Among them are Dr Radjiman Wedyodiningrat and Pangeran Ario Notodirodjo.

Their names and pictures are inscribed in the book, Vrijmetselarij en samenleving in Nederlands-Indië en Indonesië 1764 – 1962 (Freemasonry society in the Dutch East Indies and Indonesia 1764-1962), written by a Dutch Mason named TH Stevens, in 1994.

Influential men

“As an organization, Freemasonry didn’t have anything to do with Budi Utomo,” Sam Ardi said. “But it’s true that its members held important roles in Budi Utomo.”

“And we all know that Budi Utomo is considered the pioneering force behind Indonesia’s revival.”

Radjiman, who chaired the youth organization in 1914 - 1915, also became a member of the Agency for the Preparatory Work for Indonesian Independence (BPUPKI), which formulated Pancasila as the basic ideology of this country in 1945.

An Indonesian branch of the society, named Tarekat Mason Indonesia (Indonesia Freemasonry Branch), was born on April 7, 1955.

Among the high-ranking officials in the organization was Indonesia’s first chief of police Raden Said Soekanto Tjokrodiatmodjo. According to the book Tarekat Mason Bebas dan Masyarakat di Hindia Belanda dan Indonesia 1764 – 1962, Soekanto was a grandmaster in the organization.

Visit to the graveyard: JH Horst's former grave, with a huge skull and crossing bones, etched on his tombstone. (JP/Sylviana Hamdani) (JP/Sylviana Hamdani)Stigma

Even though many of its members held key roles in vital institutions in Indonesia, Freemasonry was eventually banned in the country.

In 1962. Sukarno issued Presidential Decree No. 264/1962 that banned the society, together with seven other organizations.

“Based on the legal document, Freemasonry was banned as its values were deemed unsuitable with Indonesia’s national identity,” Sam Ardi, who is currently studying for a law doctoral degree in Diponegoro University, Semarang, said.

Almost four decades later, the decree was revoked by Gus Dur with Presidential Decree No. 69/2000.

And yet, Freemasonry has never resurfaced in Indonesia.

“Indonesian Masons have decided not to propose for a new permit for their organization as there is already a strong stigma against Freemasonry and its members in this country,” Ardi said.

According to Ardi, there are currently “below 100” members of Freemasonry in Indonesia. They belong to lodges in Singapore, Australia, Philippines and The Netherlands.

Freemasonry seems to be more open to the public in this modern era.

According to the historian, many Freemasonry lodges around the world opened the doors of their lodges for public vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It’s in line with the society’s main goal of enhancing humanity,” Ardi concluded.