Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

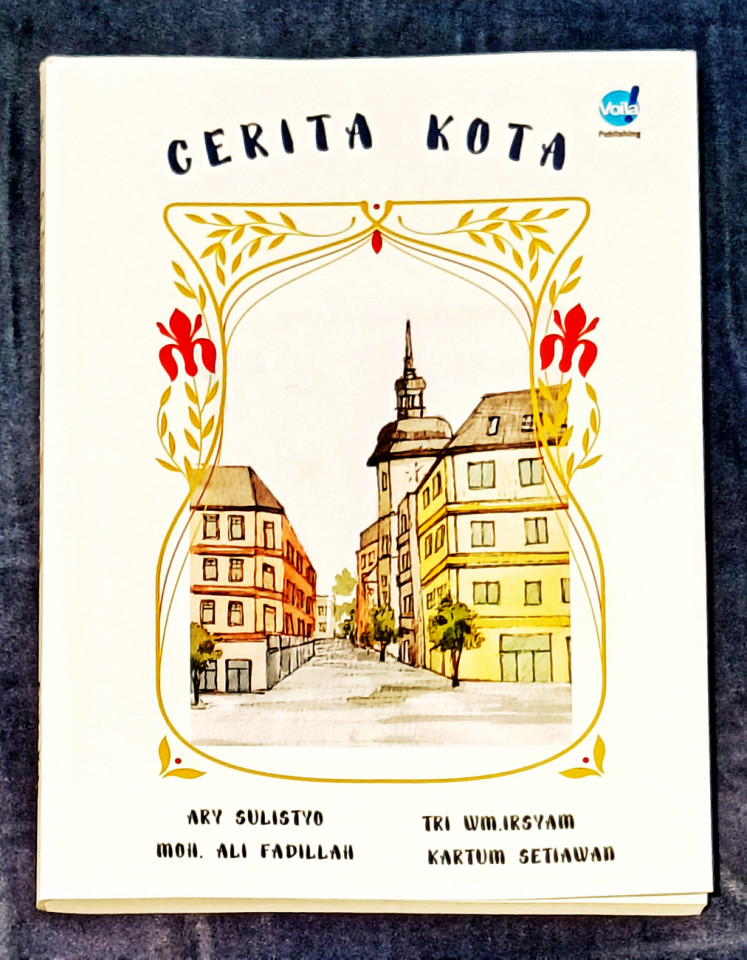

View all search results‘Cerita Kota’ tells the good and bad of Jakarta

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Four Indonesian archeologists and historians have worked together to reveal exciting parts of the city’s history.

Jakarta never ceases to entice – or repulse – many. Rows of glitzy skyscrapers and tree-lined boulevards in the capital’s central business districts showcase affluence. And yet, many of its 10 million inhabitants are forced to exist in its dark and smelly alleys.

Nevertheless, the city has never lost its charms over many centuries.

“Seen from any angle, Jakarta is always interesting,” historian Kartum Setiawan told The Jakarta Post during the launch of the book Cerita Kota (Tales of the City). The event was held at the Jakarta Maritime Museum in North Jakarta on Oct. 22. “Then and now, the city has always had a strong appeal.”

Kartum, a museum assessor at the Education, Culture, Research and Technology Ministry, has always been intrigued by the city and its complex history. The historian collaborated with three colleagues – archeologist Ary Sulistyo, archeologist Mohammad Ali Fadillah and historian Tri Wahyuning M Irsyam – in writing Cerita Kota.

“We see Jakarta as pages of history,” Ary Sulistyo said. “And in this book, we try to reconstruct some [of those pages] in a way that today’s readers will relate to.”

The writers deliver the 186-page book in concise and easy-to-understand Indonesian. Ancient maps, tables and black-and-white pictures of the capital enhance its contents.

It took only three months for the authors to complete the book.

“We’ve previously conducted much research and studies on the capital. Thus, we’ve had enough data to write the book,” Kartum said.

The book is indeed laden with information. Its 20-page bibliography lists many books, journals, studies and theses from Indonesia and abroad.

“Thankfully, the book is written like a popular novel,” Nofa Farida Lestari, founder of the Indonesia Hidden Heritage Creative Hub, an independent institution that promotes historical tourism in the country, said during the book launch. “Every part of it is interesting and prompts us to read until the last page.”

Different perspectives between authors, archeologists and historians also enrich its contents.

“Archeologists see history from its tangible remains,” said Ary, archeologist of the directorate of cultural preservation and determination of Indonesian cultural heritage at the culture ministry. “On the contrary, tangible remains are not very important for historians as they can deduce [history] from archives and written records.”

Signing session: Kartum Setiawan signs a copy of 'Cerita Kota' after the book launch at the Jakarta Maritime Museum in North Jakarta on Oct. 22. (JP/Sylviana Hamdani) (JP/Sylviana Hamdani)A big kampung

The book opens with a story of a married couple that lives and works in Jakarta. The husband takes the city’s electric train (KRL) to commute daily to his office. And when he has to work overtime and return home late, his spouse, a housewife, frets about his safety and texts him continually.

The story unveils many problems Jakartans face each day, including the capital’s sprawling size, worsening traffic and increasing crime rates. And in the midst of it, ordinary men and women are just trying to make it in the city.

“Jakarta used to be a big kampung,” Ary said. “It has gone through many evolutions since then.”

In the early centuries AD, the Sunda kingdom established a port in the coastal area of what is now Jakarta and named it Calappa. The book features a wealth of archeological evidence from the period, including findings in the Buni excavation site in Bekasi, West Java.

“At that site, archeologists discovered thousands of pottery remains, which have very similar designs as those found in Arikamedu, India,” Ary said.

These rouletted pottery dates approximately to the first century AD.

“Just imagine, the city was already inhabited in that era,” the archeologist said. “And its inhabitants were already doing business with international traders.”

Many of these international traders then built settlements along the banks of Ciliwung River and lived there, prompting a massive acculturation and assimilation process among the inhabitants.

“Therefore, we now have so many kampung in Jakarta, such as Kampung Bandan, Kampung Pecinan and Kampung Pekojan,” Kartum said. “And yet, there are almost no more [monoethnic] Arabic, Bandanese or Chinese people in these kampung. They’ve all mixed through intermarriage while keeping some parts of their original culture.”

Rise from the ashes

Over the years, the port town became a vital hub for the spice trade in the archipelago, enticing people from many parts of the region and world to seek to possess it.

To secure their position against Demak, which was ambitiously expanding its kingdom, Sunda struck an agreement with Portugal, allowing the European country to land ships and build a fortress in Calappa in return for protection of the port town.

As a sign of their agreement, a monument was built at an estuary of the Ciliwung River. This was where the Portuguese planned to make their fortress. A picture of the stone monument, now stored at the Jakarta National Museum, is also featured in the book.

Demak, however, saw this agreement as a threat. Therefore, the kingdom sent a military commander, Fatahillah, to conquer the city.

After a long and fierce battle against the Portuguese army, Fatahillah conquered Calappa on June 22, 1527, and changed the town’s name to Jayakarta. Today, June 22 is celebrated as the city's anniversary.

The port town continued to prosper under the rule of Demak. With special concessions, British and Dutch traders were allowed to build their headquarters and warehouses in Jayakarta. Over the years, rivalries between these traders got fierce, prompting Jan Pieterzoon Coen, governor-general of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) to attack the city and burn it to the ground.

“But like a phoenix, Jakarta has risen from the ashes and transformed to be even stronger,” Ary said.

After his conquest, Coen renamed the city Batavia and made it the VOC’s headquarters in the archipelago.

Cover story: The cover of 'Cerita Kota' portrays Jakarta's Kota Tua area. (JP/Sylviana Hamdani) (JP/Sylviana Hamdani)‘Kota Juang’

The city also played a pivotal role in Indonesia’s fight for independence.

“Jakarta is also known as Kota Juang [City of Fighters] as there were a lot of key historical events for Indonesia’s independence that took place in the city,” Kartum said.

The book also tells the story of Si Pitung, a Betawi Robin Hood, who robbed wealthy Dutch landlords and distributed their wealth to the poor.

“Si Pitung is Jakarta’s legendary hero,” Kartum said. “His brave acts inspired courage and embodied the Betawi people’s fight against the colonialists.”

Based on the historical records detailed in the book, Si Pitung is more than just a legend. Even though no one knows his true identity, Si Pitung’s attacks were recorded in the Bataviaasch Handelsblad newspaper in 1892.

“The book indeed improves our knowledge of the city,” Mis’ari, head of the Jakarta Maritime Museum, said during the book launch. “And I’m sure that the more we know [about the city], the more we’ll love and appreciate it.”

The Jakarta Maritime Museum also houses several copies of the book in its library on the second floor.

The book also details the development of train networks in the city, which were first initiated by the Nederlandsche Indisch Spoorweg Maatschappij (NISM) in 1871. This network would then grow into today’s KRL, LRT and MRT.

“By reading it, readers will know that the idea for today’s KRL, LRT, and MRT had been conceived and planned for quite a long time,” Kartum said.

“There’s so much energy flowing to and from Jakarta each day,” Ary said. “And as long as it continues, the city will never die.”