Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsThe economics of stunting: Provide food not brochures

To cure children who have already been diagnosed with stunting we should admit that promotions, trainings and campaigns will be less effective or even useless.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

W

hen I traveled to three different Indonesian provinces earlier this month, I realized they had an unusual resemblance. Their roads were decorated with huge billboards, where photos of their local leaders were placed, ornamented with their popular tourist spots and a statement: “Eliminate stunting before 2025.”

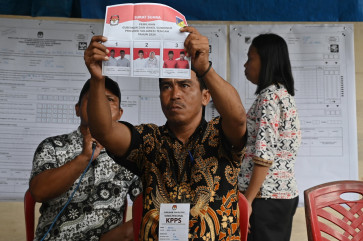

Indeed, the elections are just about to start. Providing information related to stunting can be used as a campaign tool, especially with increasing public health policy expectations from society after the COVID-19 pandemic. However, what are the proposed policies from these advertisements?

A Statistics Indonesia (BPS) survey in 2021 shows that the population of children aged under five reached 30.83 million. Unfortunately, 24.4 percent of children or around 7.5 million are stunted (the Indonesian Nutritional Status Survey, 2021). Hence, Indonesia only succeeded in reducing 6 percent of stunting in this age group in the past three years (in 2018, 30.8 percent of children aged under five were stunted).

The Medium-Term National Development Plan has targeted further cutting of the stunting rate to 14 percent in 2024. The government aims to eradicate stunting in children through five pillars, namely commitment, communication, convergence in all stakeholder levels, food security and strengthening innovation in research.

In my personal opinion, these pillars have been widely implemented except for the fourth one. The health training, inter-agency meetings, grassroot campaigns and academic conferences have been routinely conducted. However, only limited discussions and interventions in food security have emerged.

A simple proof can be seen in our Posyandu (integrated healthcare center) programs. They explain a lot about stunting initiatives, but what kind of food do they provide during the program? Is the food aimed for the children or the caregiver? Does the food consist of balanced macro and micronutrients?

Similarly, we are still struggling to find documented data about food security and specific nutrition intervention programs in the country. The majority of our stunting-related studies are focusing on its social determinants.

It is absolutely necessary to understand that lower maternal education, a higher number of household members and living in rural areas are risk factors of stunting. However, when we meet stunted children, should we send their mothers back to school, distribute their household members and move them to less rural areas?

This is when the understanding of preventing stunting and curing stunted children are becoming biased. Those social determinants will be impactful to be used in long-term stunting prevention programs, in particular to prevent new stunting cases.

Still, for short-term management and to cure those who have already been diagnosed with this condition, we should admit that these promotions, training and campaigns will be less effective or even useless. The only possible way to ameliorate their growth curve to place above the red line is by providing nutritional food.

This issue should not be further neglected. The government has warned of a possible food crisis, therefore rice imports are needed. However, can these imports be sustainable?

In the face of uncertainty, especially the imminent global recession, it will not be impossible for nations with higher supplies to prioritize their internal demands, while holding back trade, as prices slowly surge. Furthermore, Indonesia should prepare for the worst, due to our nickel dispute with the European Union. Any sanctions can lead to food security disruptions and the underprivileged, who are also strongly associated with higher prevalence of stunting, will be hit hardest.

What have we done? We are still focusing on community empowerment to overcome this stunting problem, ranging from distributing brochures to creating billboards.

If we want to prevent a parasitic worm infection, we give oral antiparasitic medicine every six months and spread information. If we want to eradicate polio, measles, diphtheria or pertussis, we utilize vaccines and distribute information. We respond to dengue outbreaks with fogging and distribute the larvicide (known as Abate) and information. We even have a strong regulation to fortify salt with iodine to prevent hypothyroidism that may lead to cognitive impairment.

Nevertheless, when we talk about stunting, we provide only repetitive information.

In a Lancet publication titled “Economic costs of childhood stunting to the private sector in low and middle-income countries,” the authors predict that Indonesia would lose US$1 billion per month due to stunting. Furthermore, they discovered that for every $1 investment in stunting intervention, the return would multiply to $81.

The costs do not take effect later in life from future health-burdens. It is happening now! To illustrate this, let’s change the word “stunted” with “hungry.” Can hungry children concentrate on their studies? Do hungry children have good sleep quality? Can hungry children be creative and innovative? In the end, we will lose many highly skilled future problem-solvers.

Countries with a higher human development index seem to understand this better. Therefore, schools in many developed nations provide meals. Their school canteens also serve as a living laboratory in which research on childhood nutritional interventions are widely conducted. Food security and nutrition imbalance are not challenges limited to developing nations.

Now, where is Indonesia’s policy standing? Unfortunately, the latest food provision at schools took place during the New Order era. Such a program could be controversial in the current point of view. However, a food provision program can be a tool to deliver diversity of diet, improve feeding practices and encourage better food preparation.

A rather rough calculation suggests that if we provide a meal three times a day at a cost of Rp10,000 (64 US cent) each for these 7.5 million stunted children, we spend less than Rp 7 trillion a month, which is only half of our stunting-associated economic loss.

If we continuously invest in food provision programs, how much money can we save in years? Needless to say, it is definitely a risky initiative, especially when we discuss how a program should be funded. But if we are able to manage it properly, it will prosper us in later years. High risk, high income, isn’t it?

Many nongovernmental organizations, communities and institutions have started programs akin to food provision on a smaller scale. Nevertheless, gathering their scattered data is another challenge. We need a more extensive calculation from experts on nutrient dose-related intervention and cost-effectiveness until future projections provide more rigorous evidence.

Furthermore, as the food security program may go beyond our borders, Indonesia should strengthen international dialogue, agreements and meetings about food security with governments, businesses and peoples. We should use our potential and opportunities to ensure food security.

Once a collaboration has been set, it should also include the transfer of knowledge and technology to improve our food availability that involves the production, distribution, and stock saving as well as providing nutrient-dense foods. Moreover, the climate-friendly approach should be propagated to ensure environmental and ecosystem sustainability, which will allow Indonesia to achieve not only food security but also food resilience.

***

The writer is a medical doctor on Tidore Island, North Maluku, and a research assistant in the Health Management and Policy Department in the Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, at Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta.