Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsRed tape stalls remote area electrification

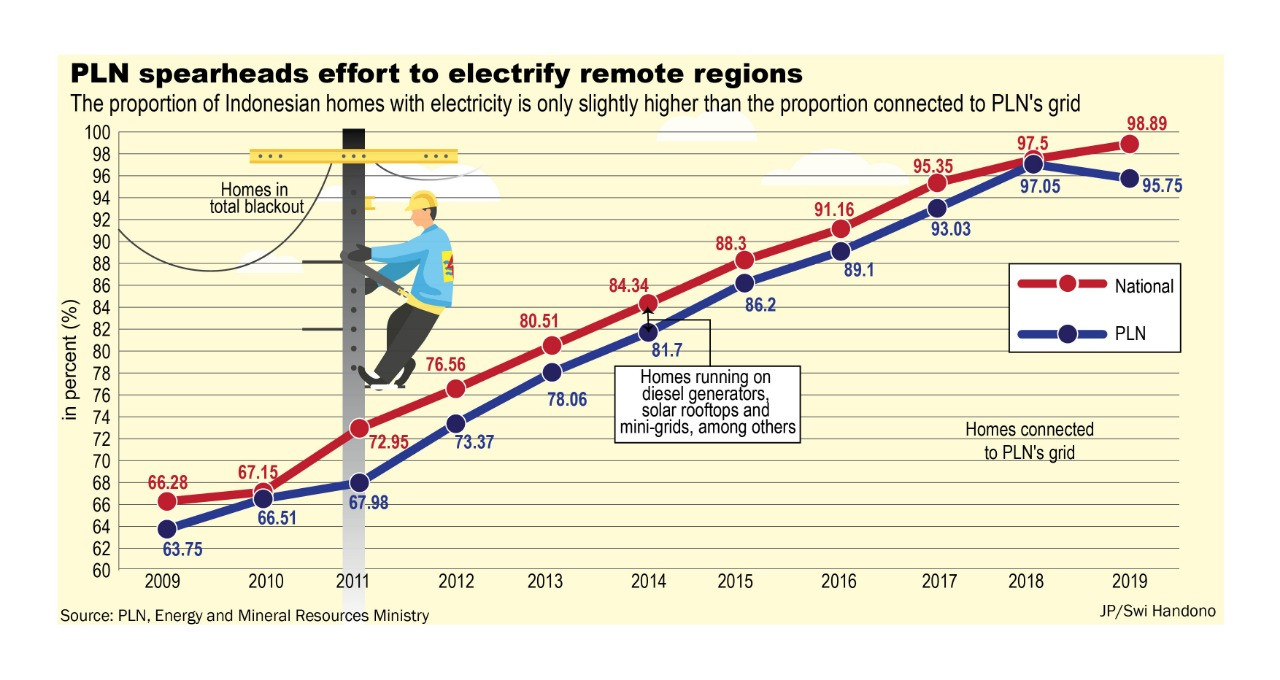

The government prioritizes PLN, the country’s legally monopolistic but cash-strapped power distributor, while crowding out private enterprises.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

P

rivate companies across the country are struggling against government regulations as they attempt to provide isolated regions with clean energy, partly due to strict government policies that often prioritize state-owned electricity firm PLN, despite the latter’s limited funds.

In Sumatra, start-up PT Surya Utama Nuansa (SUN) and region-owned enterprise (BUMD) PT Bungo Dani Mandiri Utama planned to electrify 19 villages in West Tanjung Jabung, the second-most impoverished regency in Jambi, according to Statistics Indonesia.

SUN and Bungo Dani planned to sell electricity at Rp 3,500 (25 US cents) and Rp 4,000 per kilowatt hour (kWh), much cheaper than the Rp 6,000 per kWh that most villagers were paying for diesel-generated electricity.

The companies had secured approval from various regional bodies but then, on Nov. 7, in a letter seen by The Jakarta Post, the Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry rejected their application for an area electrification permit.

The ministry wrote that PLN would connect all 19 villages by June this year but that only happened on Nov. 12. Furthermore, the regency capital Kuala Tungkal PLN head Rizki Tungguan said the electricity had not yet been turned on, due to politicization concerns amid ongoing regional elections, and that the grid’s electricity was insufficient to meet demand.

“It’s like PLN is being forced to electrify the villages. Would it not be better to reconsider?” SUN’s Verry told the Post, recollecting the companies’ plea to the energy ministry.

SUN’s case reflects the government’s approach to electrifying remote areas that, many experts say, risks undermining the country’s ability to empower millions of off-grid, low-income homes – the proverbial “last mile”.

The approach prioritizes PLN, the country’s legally monopolistic but cash-strapped power distributor, while crowding out private enterprises and even a BUMD.

The government’s PLN-first policy is based on the 2009 Electrification Law that grants PLN its monopoly – with exceptions by request – but also obliges the company to electrify the archipelago’s unreachable corners.

However, PLN struggles financing grid expansion into the last mile as it throws cash and capital into developing new coal-fired power plants (PLTU), despite a lingering power overcapacity, particularly in the Java-Bali region, at the behest of the government’s 35-gigawatt (GW) expansion program.

PLN could only finance one-fifth of the estimated Rp 11 trillion to electrify the country’s last mile, the Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry’s electrification director general, Rida Mulyana, said on Feb. 6.

The COVID-19 pandemic further deteriorates PLN’s cash flow as the company disburses pandemic relief worth millions of dollars. PLN posted a Rp 12.2 trillion loss in the January-September period, turning around an Rp 10.8 trillion profit from the same period last year.

“By default, when electrifying villages, it is always PLN even though PLN will not always have the financial capacity to electrify villages or consider it a priority,” said energy analyst Fabby Tumiwa of the Institute for Essential Services Reform (IESR).

“Meanwhile, there are a private company and a BUMD that are able to provide reliable and competitively priced electricity sooner but that are blocked by electrification area regulations,” Fabby added.

Like SUN and Bungo Dani, green energy developers PT Akuo Energy Indonesia (AEI) and PT Listrik Vine Industri (Electric Vine Industries) also faced policy hurdles while trying to electrify remote villages in East Kalimantan and Papua, respectively.

AEI managing director Refi Kunaefi said the company had secured the permits for its projects in Berau, Kalimantan, after following the energy ministry’s recommended rate of Rp 1,400 per kWh, in line with base electricity rates, but lower than the initially proposed Rp 1,800 – Rp 2,000 per kWh.

“We aren’t making any money from our operations. These three years, we’ve been making operational losses,” he told the Post. “We consider this the cost of learning to enter the industry.”

Meanwhile, Adaro Power, a subsidiary of coal mining giant Adaro Energy and a 25 percent shareholder of Electric Vine, confirmed on Nov. 18 that the green energy developer was still securing permits for its projects in Papua, which were kicked off in 2017.

“Many challenges remain in its implementation, but Adaro continues communicating with PLN,” said Adaro Power deputy president director Dharma Djojonegoro in a statement.

Several global institutions have criticized government policy for blocking private investment into green electrification projects for remote villages. These include the Asian Development Bank, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and, most recently, the International Energy Agency (IEA).

The IEA wrote in a recent report that, with COVID-19 relief programs straining public financing, “mobilizing new private sources of finance, especially for renewables, will be critical” in providing green electricity across Indonesia.

The government responded with some regulatory changes but, as Indonesian Renewable Energy Society (METI) chairman Surya Darma explained, the lingering problem was the electricity rates.

Privately-funded projects could not compete with PLN’s low base electricity rates, which are heavily aided by electricity and fossil fuel subsidies.

The government’s populist preference to keep on-grid electricity prices as low as possible, down to Rp 415 per kWh, maximizes public affordability but makes privately funded green energy projects financially unsustainable.

“There is unfair treatment between renewables and fossil fuels,” said Surya.

- Jon Afrizal contributed to this story

- The article is funded with AJI Journalist Fellowship Program 2020